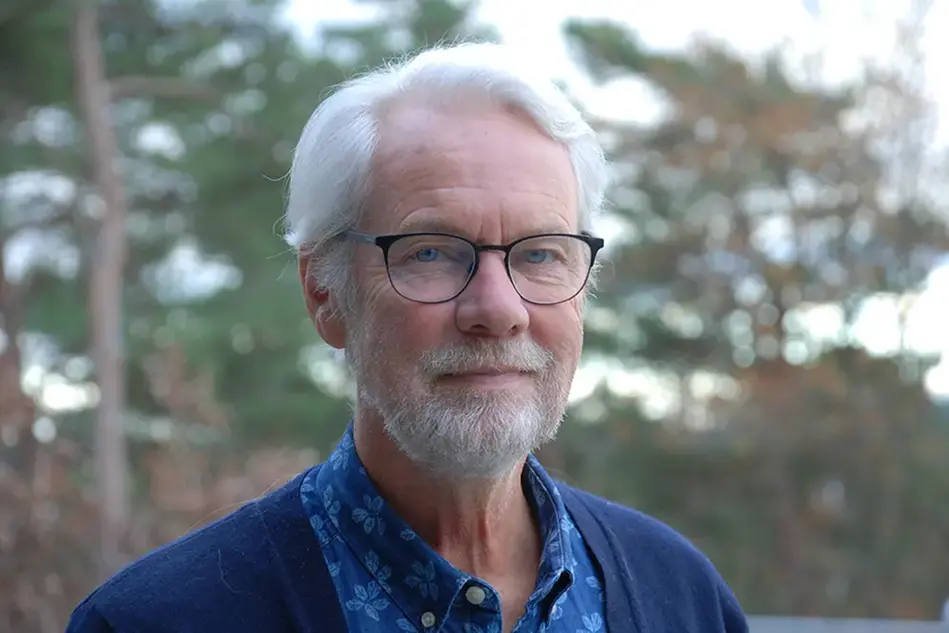

“The soul is still there” – Bertil Svensson followed Halmstad University from the start

When Bertil Svensson had just received his doctorate and started working at Halmstad University, no research was conducted there at all. For three decades, he followed and led the development towards establishing strong research centres at the University.

Anniversary portrait. During the University's 40th anniversary, we honour individuals who have been significant in the development of research and collaboration. In this portrait, you meet Bertil Svensson, one of the first members of staff with a PhD.

“My impression is that much of the original idea remains at Halmstad University to this day. That you want to work close to industry, but also close to, for example, health care, so that you really mean something to society.”

Bertil Svensson

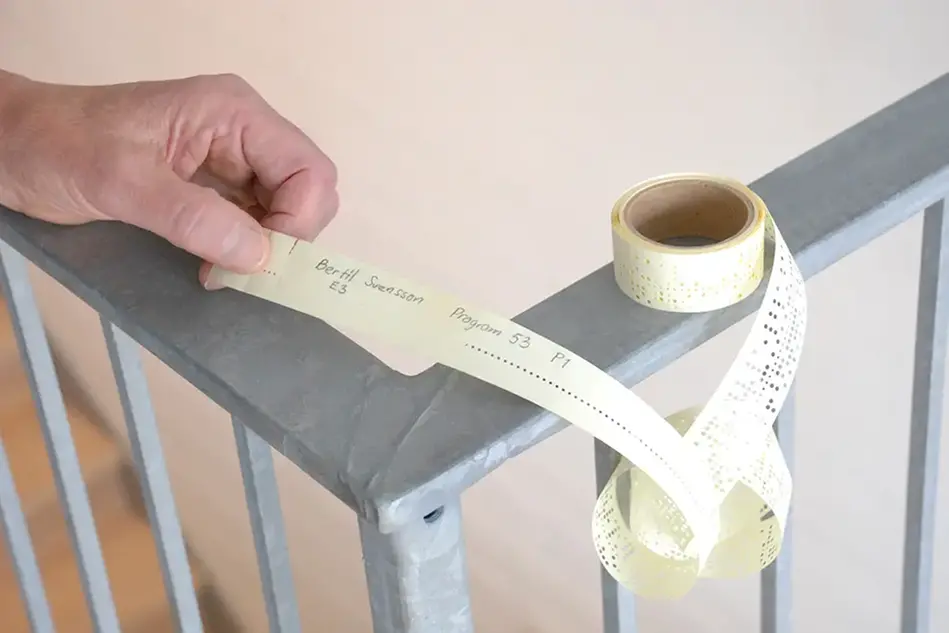

Bertil Svensson rolls out a few inches of a long strip of paper, full of punched holes. On it, neatly written in felt-tip pen, is: "Approved." Next to it in pencil is: "Bertil Svensson. E 3. Program 53, P1"

“I wrote this computer programme in my third year. This kind of strip had to be punched to program SMIL, the number machine in Lund, which was the only computer available at the Master’s Programme in Engineering.”

He smiles a little as he shows the find from one of the boxes from his student days. Computers and programming have developed a bit between the 1960s when he started as a student and today. Bertil Svensson retired in 2015, and had then been affiliated with Halmstad University for over thirty years. It was the early 1980s when, as a doctoral student in Lund, he saw that Halmstad was looking for a senior lecturer for a university that did not even exist yet.

In the past, programming was done using punched holes on a paper strip.

“It sounded exciting, of course, to build something completely new. On 29 April, 1983, I defended my thesis on the parallel computer Lucas, which my PhD colleagues and I had built in Lund. Two days later I started my employment in Halmstad.”

Bertil Svensson did not only become Senior Lecturer but also Deputy Vice-Chancellor. The University initially had just under 40 employees, of which only Bertil Svensson and one other had received their doctorates.

“At first, there were no plans to create research activities, but only to educate. But I liked that. I had been a substitute Senior Lecturer for several years in Lund, so I had a lot of teaching experience.”

First in the country to have a mechatronics programme

Even before he was hired, he had had assignments in Halmstad. The foundation for Halmstad University was the post-secondary education that had already existed in Halmstad for a few years. There were three programmes; for recreation educators, preschool teachers and innovation engineers. The innovation engineers specialised in product development – identifying problems and opportunities together with industry, evaluating the appropriate technology and training to run innovation projects. But to meet the demand from the industry, there were ideas for another programme, which went more in-depth with new technology and also included more electronics.

A year before Halmstad University was started, Bertil Svensson, together with Göran Gremyr, who was a Senior Lecturer for Halmstad's innovation engineers, had been commissioned to develop the new programme. The working title was "control engineering", but Bertil Svensson's LTH colleague Freddy Olsson, who had designed Halmstad's Innovation Engineering programme, suggested that the new specialisation should be called mechatronics. The term came from Japan and had begun to settle in other countries. In Sweden, Halmstad University was the first to call an education programme that.

“It was an exiting time. There was a settler spirit, a driving principal and freedom to do new things. At that time, it was UHÄ, now UKÄ – Swedish Higher Education Authority, that decided which programmes should exist and how many students that should be accepted. But at the new universities, it was possible to break new ground. I remember Freddy saying that he hadn't been able to start the Innovation Engineering programme in Lund, and maybe it was the same with mechatronics.”

Vice-Chancellor wanted researching teachers

Although the University did not formally engage in research, it was an issue that engaged the first Vice-Chancellor SvenOve Johansson.

“He was very adamant that there is no university if there is no knowledge development and researching teachers. So, he encouraged us to continue with projects we were already running and helped us find funding,” says Bertil Svensson.

Bertil Svensson started at Halmstad University a few months before it became an independent university.

SvenOve Johansson wanted to build centres around the University's research areas and Bertil Svensson was one of those who got to start building them. First out was the Centre for Image Processing and Computer Graphics, CBD. Conversations with industry had shown that the companies had several problems that could be solved with image analysis.

“But we didn't have anyone who knew image processing, least of all our students, because there was no course in it. That is why we formed a centre of excellence to develop the knowledge ourselves, together with the companies.”

Bertil Svensson was one of the few who had any experience in the field, and he started by holding a course for both company representatives and his own colleagues. At the same time, the University had hired a teacher with a PhD who was an expert in computer graphics, and in 1986 CBD was started.

Full time in Luleå but still in Halmstad

At the end of the 1980s, technically Bertil Svensson left Halmstad University, but in practice, he remained with one foot in Halmstad. The Vice-Chancellor of Luleå University of Technology had contacted him and asked if he wanted to build their new research area of computer technology, and then become a professor for it.

“I hadn't thought of becoming a professor anywhere, but I said yes. It was a great opportunity. It was a full-time job, but I was happy to have part of my business further south and commute between workplaces. Many in Luleå did so.”

Bertil Svensson kept some research in Halmstad and spent every other week there, every other week in Luleå as Acting Professor. His wife and children remained in Halmstad, in the home that was so close to the airport that Bertil Svensson walked there when it was time to travel to work. It worked well, he thought, and even better when over time he switched to spending only a few days every three weeks in Norrbotten. When the permanent professorship in Luleå was announced in 1991, he applied for it, but at the same time was asked by Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg to apply for a corresponding position there. He did and was offered both.

“It was really hard to choose, but I had to. Although I liked Luleå University of Technology very much, I chose Chalmers. They were so eager and committed to what I was doing and there were young scientists there working in the same direction as me.”

Knowledge from Halmstad shaped Chalmers’ education

During his time in Gothenburg, Bertil Svensson supervised doctoral students not only at Chalmers but also at Halmstad University, which at that time had no doctoral education of its own. The new Chalmers professor was also given an unusual task: he was asked to remake the Master’s Programme in Computer Engineering considerably.

“It was part of a national initiative, with strong support from Chalmers’ management. They wanted to see a revolution. The education should be so interesting that even girls would choose it!”

Bertil Svensson smiles. One of the first things he did was to take his Chalmers colleagues to Halmstad University for a visit. With inspiration from Halmstad and expertise from Chalmers employees, they redesigned the programme in Gothenburg. Instead of detail-oriented, somewhat nerdy courses that mainly attracted those who love programming languages, an education was developed that put the detailed knowledge in context. In what way could computer technology benefit society? The students had to reflect on what they thought computers would contribute with both in the present and in the future. They began to work in groups and plan their own projects.

“The colleagues never thought that would happen at Chalmers, that someone would change education so much. It wouldn't have been as good without my experience from Halmstad,” says Bertil Svensson.

No traditional University

In 1997, Halmstad University applied for its own professorships, and the following year Bertil Svensson applied for, and received, one of the first professorships. Leaving Chalmers meant putting some opportunities behind him, he says. At a large, well-known university, you automatically get a good connection with the world, and it was easier to find research funding. But Halmstad had other advantages. It was easier to achieve interdisciplinary collaborations at a small university where there was a close gap between the special skills. Many employees came from other universities and other countries, and their experiences merged into something new. At larger universities, a department could instead be populated by people who had stayed in the same place for many years, first as students, then as licentiate students, doctoral students, and lecturers.

“Halmstad was not a traditional university in that way. And through recruitment from abroad, we built a network of contacts with top universities such as Berkeley, MIT and ETH. I think that meant a lot for us.”

Halmstad University also started to make things easier in terms of research funding at this time. An important reason was the formation of the Knowledge Foundation, the Foundation for Knowledge and Competence Development. It was part of a handful of research foundations created from the discontinued employee funds and part of its mission was to increase contact between industry and academia.

“It was a chance for us in Halmstad. We had the trust of the industry already; they knew we were making things happen. Through the Knowledge Foundation, we gained access to money that not even Chalmers had,” says Bertil Svensson.

So, from the turn of the millennium there was not only start-up spirit and interdisciplinarity, but also research funding. The system of centres that had been in place from the beginning also motivated collaborations, according to Bertil Svensson. Any researcher who came to Halmstad basically had to find someone to collaborate with, and this created new, unconventional approaches.

“My impression is that much of the original idea remains at Halmstad University to this day. That you want to work close to industry, but also close to, for example, health care, so that you really mean something to society. I think the soul is still there, that you want to be a little different.”

Text: Lisa Kirsebom

Photo: Roland Thörner and archives