“The highest level is when research has political influence”

Professor Emerita of Sport Psychology Natalia Stambulova was the first in the world to study several transitions within the athletic career, including the one from junior to senior sport. After almost fifty years of research and working to support elite athletes, she is far from tired of her subject. Natalia Stambulova is one of those who, through her successful research, has really contributed to developing Halmstad University's research and putting the University on the world map.

Anniversary portrait. During the University's 40th anniversary, we honour individuals who have been significant in the development of research and collaboration. In this portrait, Natalia Stambulova tells the story of how she went from figure skater to internationally renowned research profile.

“I don't know if it mattered so much to me that I was the first female professor, but I understand that it could matter to others because there was a need for female role models.”

Natalia Stambulova

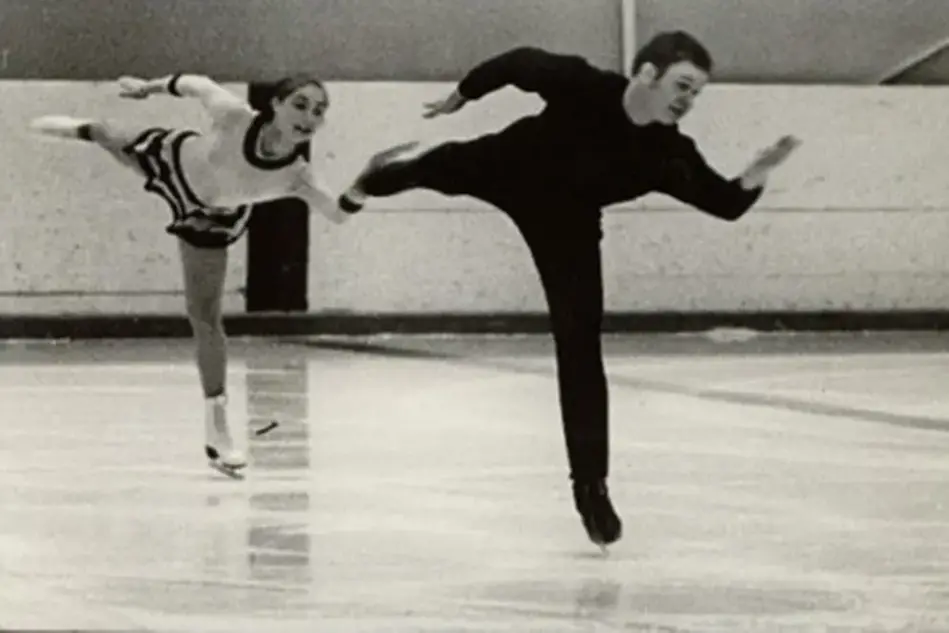

In her youth, Natalia Stambulova was a junior champion in pair skating in her former home country, the Soviet Union. Photo: Private

“I've only ever had two employers, first the St Petersburg Sports University named after P. Lesgaft, then Halmstad University, and I've been here for over twenty years. As a professor in Russia, I could never have imagined the international career I would have. I am so grateful for the support here that has made it possible to achieve so much,” says Natalia Stambulova.

In 2002, she became the first female professor at Halmstad University. Since the turn of the year, she is Professor Emerita, still active in several research and publication projects. Her subject is Sports Psychology with a focus on, among other things, dual careers and transition periods in life. It has been about the transition from junior to senior sport, from amateur to professional, or from a time as a star to a life as a 'retiree' from sport.

Own elite career sparked interest

Natalia Stambulova was born in 1952 in what was then Leningrad in the Soviet Union. She started training in figure skating at the age of six, and her entire childhood and teenage years were characterised by the sport.

“Of course, school had to be taken care of, but it always felt easy,” she says.

In 2019, Natalia Stambulova received the prestigious Ema Geron award at the European Congress of Sport Psychology. Here surrounded by her colleagues from Halmstad University. Photo: Private

It was figure skating that was the challenge. She became a pair skater and in 1969 she and her partner won the Soviet junior championship. They became members of the senior team but never competed in the biggest international competitions.

“The competition within the national team was high and we were ranked six or seven internally, so we only participated in national and some minor international competitions. But it was still an experience of sporting life at an elite level, and it made me interested in sports science.”

Natalia Stambulova started studying at “the Lesgaft University”, the country's oldest sports university. Thanks to a good psychology teacher, her interest in sports psychology soon piqued. At the time, she had a dual career of the kind she would later research, as a university student and an elite athlete – but her sporting career ended at the age of 20 due to a serious injury.

“I needed to shift my focus to other things. I had my studies, and I got married and had a daughter. Everything happened quite quickly, and I was busy, so it wasn't as big a crisis for me as it might have been,” says Natalia Stambulova.

Challenging transition from junior to senior

After completing a master's degree, she was offered a position as a doctoral student and completed her PhD degree in 1978, after which she rose through the ranks and became a full professor in 1996. The overall topic was always developmental psychology in sport, but she gradually broadened her work to include more and more perspectives, including athletes’ crises and how to protect athletes’ mental health, talent development, dual career development, and studying various athletic and dual career environments.

Natalia Stambulova.

“I was the first researcher in the world to study the transition from junior to senior level in elite sport. It is an important shift. Senior competitions are much more competitive, and athletes often have to change their training regimen. I published my first article in 1994 and over time international interest in the topic grew. Now there is a lot of research in this area,” says Natalia Stambulova.

There is an inherent paradox in the transition from junior to senior, she explains:

“Almost all young successful athletes dream of an elite career and the work of coaches is about helping as many as possible to succeed. At the same time, only a minority of juniors actually become elite as adults. They are the top of a pyramid, and there is no room for more. Others quit, or switch to sport as a leisure activity. Athletes may also need help with this transition.”

Most successful junior may have most difficult transition

Those who do move on go through a complex change that affects all areas of their lives: athletically, they must adapt to new demands; psychologically, they are in a period of identity formation; and psychosocially, for many, it is a time of strong friendships and new relationships.

“In addition, as long as they are in school, they have to navigate a dual career, sometimes managing a transition to university life in parallel with the transition to senior sport. It is very challenging,” says Natalia Stambulova.

A surprising discovery was that the most successful juniors sometimes have a more difficult transition than the more mediocre ones. The reasons are both practical and psychological. The stars of junior sport fall out of step with their peers due to their rapid development, which can be difficult for coaches to deal with. Sometimes the solution is more difficult and risky training programmes for the best students, with the risk of injury and dropout. Being discovered early and promoted as a star also means that young people experience high expectations and pressure. On the other hand, those who are not at the top are allowed to develop in peace and quiet, which can sometimes lead to better success in the long run.

Was told about Halmstad

Despite successful research and growing international recognition, just a few years into her professorship, Natalia Stambulova felt her career starting to stagnate. She would not be able to grow as much as she hoped if she stayed in Russia, and the country's recurring political and economic crises contributed to her decision to seek a position elsewhere in the world. For language reasons, she initially considered English-speaking countries, but in 2000 she received an unexpected tip. Halmstad University organised a conference on sports psychology where several of Natalia Stambulova's research friends participated, and afterwards some of them contacted her saying that there was a good group of people looking for new colleagues internationally.

“‘Sweden?’, I thought. ‘I don't know a word of Swedish.’ But they said that English was not a problem, so I applied for a senior lecturer position and got it in 2001.”

Just one year later, she became the first woman to hold a Swedish professorship at Halmstad University.

“I don't know if it mattered so much to me that I was the first female professor, but I understand that it could matter to others because there was a need for female role models. Already in the same year, two other female professors were appointed, and today there are many.”

Results are meant to be disseminated

The move to Sweden was challenging in many ways, but Natalia Stambulova praises the University and her colleagues for the support she received both professionally and privately. The world opened up to her in a new way and the coming decades saw a wide range of national and international research projects, publications, awards and involvement in international organisations.

She has received many awards for her research.

When the European Commission decided to develop EU Dual Career Guidelines, it was Natalia Stambulova who represented Sweden in the process.

“It was a very interesting experience. We were one to two representatives from each country in a very mixed group, including researchers, practitioners, some from the Olympic Committees.... It was complex, but we succeeded. In 2012, the Guidelines were published.”

In 2018, Sweden became the first country in Europe to develop national guidelines for elite athletes' dual careers, and Natalia Stambulova was one of the researchers who contributed to the work. The result was, among other things, a system where higher education programmes are designed to fit in with an elite career, at universities designated as either National Sports Universities (Halmstad University together with Malmö University form one of them) or Elite Sports Friendly Universities.

“Research results are meant to be disseminated through publications and then implemented, and the highest level of implementation is when the research has political influence. This is what we have achieved,” Natalia Stambulova says.

No plan to stop completely

As Professor Emerita, she only does what she enjoys most. She continues writing sport psychology papers and working as an associate editor for Psychology of Sport & Exercise and International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, and guest editor for Journal of Sport Psychology in Action.

“It's nice to be free from all the routine work and to be able to continue just because I enjoy the job and my colleagues. I am now participating in a four-year national research project in collaboration with the Swedish Sports Confederation. In this project, a research team from Halmstad follow student-athletes' experiences of a dual career and evaluate the support provided in Sweden. I am proud that my former PhD students Alina Franck, Johan Ekengren, and Lukas Linnér successfully continue internationally visible athlete career research at Halmstad University.”

Natalia Stambulova does not know how and when she will stop research altogether:

“The years here in Halmstad have been the best in my career and I don't have a plan right now to stop completely. I'm not afraid of retirement, but as an expert in transitions I know that it's better to leave slowly and gradually than abruptly.”

Text: Lisa Kirsebom

Photo: iStock, Anders Andersson, Hasse Halling

Natalia Stambulova, selected awards and assignments

2004: Distinguished International Scholar Award of the Association for Applied Sport Psychology.

2009–2017: Vice President of the International Society of Sport Psychology, ISSP.

2019: Ema Geron Award from the European Federation of Sport Psychology.

2021: ISSP Distinguished International Scholar Award “in recognition of making outstanding and distinguished, long term, original contribution to the advancement of sport psychology”.